Originally posted May 25, 2009

Failure for Social Media?

Failure for Social Media?

After articles like this one in Business Week, which claim that social media has no presence in consumer purchasing considerations, I thought I would take another look at Chanel and the company’s recent cinematic commercial initiatives, which have been creating a viral extravaganza for the last couple of years.

I’m with Ruth Mortimer in thinking that luxury brands can use the avenues of digital media to provide vehicles for brand ambassadors and fans to influence consumer spending through viral marketing.

The French powerhouse has created this buzz through their short films, which are actually cinematic commercial spots that were soon followed after by Dior, Prada and others (though with less buzz).

The goal of these cinematic campaigns is to provide the greatest creative and entertainment value, which resonates best with moviegoers- a young, affluent and educated demographic that is highly valued within the advertising community. With the modern in-theater market and new technologies of dispersion, the quality of cinema advertising has soured exponentially. The challenge was to create something worthy of consideration from existing or potential luxury markets.

Stopping short of creating a Facebook page for the brand, Chanel instead focused its efforts on creating brand-worthy commercials told from the perspective of the House of Chanel, which were also considered entertainment-worthy by the fans. Fans (and critiques) took over from there, building hype, passing the video campaigns across the internet and voting, tagging and commenting on what they saw.

The immense budgets of these films shows just where the brand’s money-maker lies: fragrance.

Updating an Old Favorite

Chanel’s first commercial blockbuster was released in 2005, staring Nicole Kidman and directed by her Moulin Rouge visionary, Baz Luhrmann. With a +50 million euro budget, Chanel focused efforts on repositioning their biggest money-maker, Chanel No. 5, for a then-booming US market. (Oh, how the times have changed!)

Chanel’s first commercial blockbuster was released in 2005, staring Nicole Kidman and directed by her Moulin Rouge visionary, Baz Luhrmann. With a +50 million euro budget, Chanel focused efforts on repositioning their biggest money-maker, Chanel No. 5, for a then-booming US market. (Oh, how the times have changed!)

The brand sought to update the image of No. 5 for the American youth market, who typically viewed this fragrance as a relic from grandma’s dating years. Loaded with strong, opulent and innovative visuals, the “fashionable” director created the ad film as a movie trailer spanning more than 2 minutes. Most modern consumers associated the fragrance with the romantic lifestyle of mid-century France. In an effort to stay relevant and up-to-date, avoiding the classic undertones, the commercial is set in NYC instead of Paris, and all dialogue is in English.

Themes of romance, escapism, adventure, mystique, an example of exquisite haute couture, the use of men’s wear and even a little high/low-class rendezvous is inserted to balance the updated image with the brand history.

Various postings of the commercial short have collectively received more than 2 million views on YouTube alone, with over 1,000 comments.

The perfume continues to be one of the most widely purchased fragrances of all time.

A New Classic

Following the success of the initial campaign, Chanel developed a second cinematic commercial spot, this time to introduce a modern fragrance to capture the essence of the brand for today’s market, without interfering with the positioning of the “Old Classic,” No. 5.

Following the success of the initial campaign, Chanel developed a second cinematic commercial spot, this time to introduce a modern fragrance to capture the essence of the brand for today’s market, without interfering with the positioning of the “Old Classic,” No. 5.

The short film for Chanel’s Coco Mademoiselle fragrance focused on historic references to the brand’s namesake, Coco Chanel, using a modern actress and a timeless Parisian set. Coinciding with the launch of her 2007 movie, Atonement, Keira Knightly starred in the spot as a variation of Coco herself through imagery associated with the codes of the brand: the men’s shirt, the classic hat, the famed mirrors of Chanel’s Paris apartment, the camellias woven into a bracelet; all with a touch of elegance, sophistication and romance.

There is even a focus on mix-and-match, where the actress removes her ankle bracelet and uses it as a necklace (it contains pearls, of course). Silly, yes, but it gets the point across: this fragrance represents the modern ideal of Chanel herself.

Demonstrating less viral activity, the commercial film received fewer than half a million hits on YouTube, but the associated print ads created quite a buzz in the blog world.

Revisiting the Classic

After the success of the 2006 campaign staring Nicole Kidman, Chanel again sought to produce a blockbuster ad that would address the entire international community while building hype for the upcoming release of the biopic “Coco Avant Chanel” (Coco Before Chanel).

The 2009 commercial film features Audrey Tautou, star of Amelie and The Da Vinci Code, and is directed by Amelie’s Jean-Pierre Jeunet. Unlike the Kidman film, the Tautou version includes no dialogue, with the exception of a night train conductor asking for the starlet’s passport in French. The rich sound and visuals tell a story of an independent, young first-class traveler who falls in love with a mysterious man in her neighboring train cabin on their way from the Limoges Bénédictins station in France to Istanbul. The fellow traveler is seduced by the young woman’s scent, No. 5.

This commercial has all the entertainment value of the original Kidman spot, but aside from featuring one solitary pearl, it lacks the traditional codes of the brand. What it achieves is bringing home the message of romance to No. 5 for the international community, featuring today’s most famous young French starlet together with the classic love song, Billie Holiday’s “I’m a Fool to Want You”.

Just released this month, the film already has a combined YouTube hit rate of less than 100,000 and enough pages of comments to show that people are engaged, for better or for worse.

UPDATE:

Apparently, I missed this legal notice on Chanel’s own website, but was shocked to learn from the Business of Fashion site that the following is stated:

“No part of this website may be copied, reproduced, republished, uploaded, posted, transmitted or distributed in any way for commercial purposes. This prohibition also includes framing any content from this site on another site, as well as unauthorized linking…use of material from this site without CHANEL’s prior written consent is strictly prohibited.”

That doesn’t indicate a very clear understanding of viral marketing, does it? Frankly, I was a little surprised that the site did not offer embedding capabilities, although I understand that the brand doesn’t want their “commercial” to appear just anywhere. However, to outwardly restrict the very act that makes these videos so successful is a bit shortsighted, if you ask me!

Here’s what I want out of a luxury brand: I want the feel of the brand. I want the background story behind the items I love- how it was conceived, how it was constructed; what makes it special. I want to know what music the design team is listening to, and I want to be able to download playlists from fashion week and songs that are related to the collection, whether from inspiration or just setting the mood. If, like in

Here’s what I want out of a luxury brand: I want the feel of the brand. I want the background story behind the items I love- how it was conceived, how it was constructed; what makes it special. I want to know what music the design team is listening to, and I want to be able to download playlists from fashion week and songs that are related to the collection, whether from inspiration or just setting the mood. If, like in

French fashion has long been reflective of social and economic hierarchy, illuminating the distinction among classes. Beginning with the Royal Court of the Sun King, France became the capitol of rich fashion. After Charles Worth created the business of haute couture in the 1800s, Paris became the creative center for a business model that has evolved greatly, yet still remains centered around the spirit of haute couture.

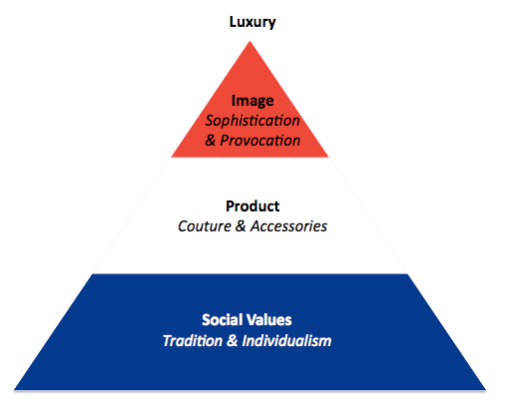

French fashion has long been reflective of social and economic hierarchy, illuminating the distinction among classes. Beginning with the Royal Court of the Sun King, France became the capitol of rich fashion. After Charles Worth created the business of haute couture in the 1800s, Paris became the creative center for a business model that has evolved greatly, yet still remains centered around the spirit of haute couture. Most companies that made their name in haute couture today sell mostly accessible products and democratic accessories like lipstick, perfumes, and so on. However, to continue to sell these more “basic” goods at high profit margins, they must continue to produce high fashion. People are now buying the legacy of couture, rather than the couture itself. Therefore, to make the big bucks selling goods at the bottom, you must be positioned at the top.

Most companies that made their name in haute couture today sell mostly accessible products and democratic accessories like lipstick, perfumes, and so on. However, to continue to sell these more “basic” goods at high profit margins, they must continue to produce high fashion. People are now buying the legacy of couture, rather than the couture itself. Therefore, to make the big bucks selling goods at the bottom, you must be positioned at the top. Brand images and communications demonstrate a high level of arrogance and provocation. Have you ever wondered how or why that “crazy stuff that nobody is ever going to buy” makes it onto the catwalk? The most elaborate and provocative designs are taken onto the runway because the goal is not mass profitability, but to demonstrate creativity and uniqueness. Consider the wild boys Jean Paul Gaultier for Hermes, or John Galliano for Dior (below).

Brand images and communications demonstrate a high level of arrogance and provocation. Have you ever wondered how or why that “crazy stuff that nobody is ever going to buy” makes it onto the catwalk? The most elaborate and provocative designs are taken onto the runway because the goal is not mass profitability, but to demonstrate creativity and uniqueness. Consider the wild boys Jean Paul Gaultier for Hermes, or John Galliano for Dior (below).

In 1946, Christian Dior (1905-1957) came on the scene, opening his own couture house. He was contacted by the French Minister of Fashion (what a title!), a man named Lucien Lelong, and asked to partner with French textile tycoon, “The Cotton King” Marcel Boussac, in order to reinvigorate the fashion and textile industries of France on a global scale. Jacques c, a young civil servant, was hired to serve as business administrator. Dior launched his first collection in 1947 in cooperation with Boussac. The collection embraced the “New Look”, which recalled the formerly popular S-shaped silhouette without the underlying cage. Dior abandoned the masculine look, and emphasized luxury and opulence. The look was indeed new after years of the plain, shapeless ration dresses of WW2, and came with huge amounts of layered textiles and embroideries. Dior and Boussac used their marketing skills to promote the extensive use of fabrics (promoting the textile industry) and opulent details and construction (promoting the fashion industry) by playing to the optimism that followed years of suffering.

In 1946, Christian Dior (1905-1957) came on the scene, opening his own couture house. He was contacted by the French Minister of Fashion (what a title!), a man named Lucien Lelong, and asked to partner with French textile tycoon, “The Cotton King” Marcel Boussac, in order to reinvigorate the fashion and textile industries of France on a global scale. Jacques c, a young civil servant, was hired to serve as business administrator. Dior launched his first collection in 1947 in cooperation with Boussac. The collection embraced the “New Look”, which recalled the formerly popular S-shaped silhouette without the underlying cage. Dior abandoned the masculine look, and emphasized luxury and opulence. The look was indeed new after years of the plain, shapeless ration dresses of WW2, and came with huge amounts of layered textiles and embroideries. Dior and Boussac used their marketing skills to promote the extensive use of fabrics (promoting the textile industry) and opulent details and construction (promoting the fashion industry) by playing to the optimism that followed years of suffering. There was a backlash to the New Look in the States in 1946-7, when people thought it inappropriate to display such opulence after such great suffering, and for women to bind themselves again after working in the place of men and revolutionizing their fashion in accordance. They weren’t the only ones speaking out against the New Look. Coco Chanel re-emerged and gave many interviews against Dior, saying that his design was an easy dress to impose on women, but that they needed to be able to be comfortable in their daily lives and be able to move independent of assistance. She remarked, “A woman should do her shopping without being teased by the housewife. Whomever laughs is always right.” (Ironically, the North American market would become Dior’s biggest by the mid-50s.)

There was a backlash to the New Look in the States in 1946-7, when people thought it inappropriate to display such opulence after such great suffering, and for women to bind themselves again after working in the place of men and revolutionizing their fashion in accordance. They weren’t the only ones speaking out against the New Look. Coco Chanel re-emerged and gave many interviews against Dior, saying that his design was an easy dress to impose on women, but that they needed to be able to be comfortable in their daily lives and be able to move independent of assistance. She remarked, “A woman should do her shopping without being teased by the housewife. Whomever laughs is always right.” (Ironically, the North American market would become Dior’s biggest by the mid-50s.)

Chanel believed that a woman could be active and still remain elegant. She put this philosophy into her designs, shortening skirts and using jersey in womenswear. Of course, jersey had previously only been used for men’s underwear and sportswear, so this was considered revolutionary at the time. Her dresses stressed the new social role played by women, incorporating simplicity and masculinity.

Chanel believed that a woman could be active and still remain elegant. She put this philosophy into her designs, shortening skirts and using jersey in womenswear. Of course, jersey had previously only been used for men’s underwear and sportswear, so this was considered revolutionary at the time. Her dresses stressed the new social role played by women, incorporating simplicity and masculinity. Chanel began diversification of her brand through the production of perfumes and jewels. In the 1930s, the constructed pins made from stained glass. Chanel was the first designer to place great importance on bijoux. She maintained one symbol from her past among “doubtful” women- the camellia, trademark flower of high class prostitutes. She turned this symbol into a luxury accessory. Jewelry was an important decorative element upon the simple, clean Chanel dress.

Chanel began diversification of her brand through the production of perfumes and jewels. In the 1930s, the constructed pins made from stained glass. Chanel was the first designer to place great importance on bijoux. She maintained one symbol from her past among “doubtful” women- the camellia, trademark flower of high class prostitutes. She turned this symbol into a luxury accessory. Jewelry was an important decorative element upon the simple, clean Chanel dress. Chanel used her own name in all matters, on all products and campaigns. With No. 5, she was selling her look and lifestyle, and therefore her branded self. This branded marketing was so effective that Chanel No. 5 remains one of the top-selling perfumes today. (The company estimates that one bottle is sold every 55 seconds.) However, the next time you are at the perfume counter with a friend, try a blind sniff test putting No. 5 up against a more modern fragrance, like Chanel’s Mademoiselle. These days, 99% of the time, No. 5 will not be appreciated unless the person smelling it knows that it is Chanel’s classic fragrance. It’s nothing against the fragrance- it’s just a bit outdated for our modern noses, and a little heavier than what most consumers today are after. Yet it flies off the shelves. That is some serious brand power!

Chanel used her own name in all matters, on all products and campaigns. With No. 5, she was selling her look and lifestyle, and therefore her branded self. This branded marketing was so effective that Chanel No. 5 remains one of the top-selling perfumes today. (The company estimates that one bottle is sold every 55 seconds.) However, the next time you are at the perfume counter with a friend, try a blind sniff test putting No. 5 up against a more modern fragrance, like Chanel’s Mademoiselle. These days, 99% of the time, No. 5 will not be appreciated unless the person smelling it knows that it is Chanel’s classic fragrance. It’s nothing against the fragrance- it’s just a bit outdated for our modern noses, and a little heavier than what most consumers today are after. Yet it flies off the shelves. That is some serious brand power!